MWINGI, Kenya (AP) — Esther Kangali felt a sharp pain while on her mother’s farm in eastern Kenya. She looked down to see a large snake coiling around her left leg. She screamed, and her mother came running.

Kangali was rushed to a nearby health centre, but it lacked the antivenom needed to treat the snake’s bite. A referral hospital also had none. Two days later, she reached a hospital in Nairobi, where her leg was amputated due to delayed treatment.

The 32-year-old mother of five knows her ordeal could have been avoided if clinics in snakebite-prone areas were stocked with antivenom. Kitui County, where Kangali’s family farm is located, has Kenya’s second-highest number of snakebite victims, according to the health ministry, which reported 20,000 cases last year.

In Kenya, about 4,000 snakebite victims die annually, while 7,000 others experience paralysis or other severe health complications, according to the local Institute of Primate Research.

Residents fear the problem is worsening. As forests shrink due to logging and agricultural expansion and climate patterns become more unpredictable, snakes are increasingly found around homes.

“We are causing adverse effects on their habitats like forest destruction, and eventually, we have snakes coming into our homes primarily to seek water or food,” said Geoffrey Maranga, a senior herpetologist at the Kenya Snakebite Research and Intervention Center. Climate change also drives snakes into homesteads, as they seek water in dry periods and shelter during wet times.

Maranga and his colleagues are collaborating with the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine to develop effective and safe snakebite treatments and produce antivenom locally. The center estimates more than half of snakebite victims in Kenya do not seek hospital treatment due to high costs and difficulty finding antivenom, often resorting to traditional remedies instead.

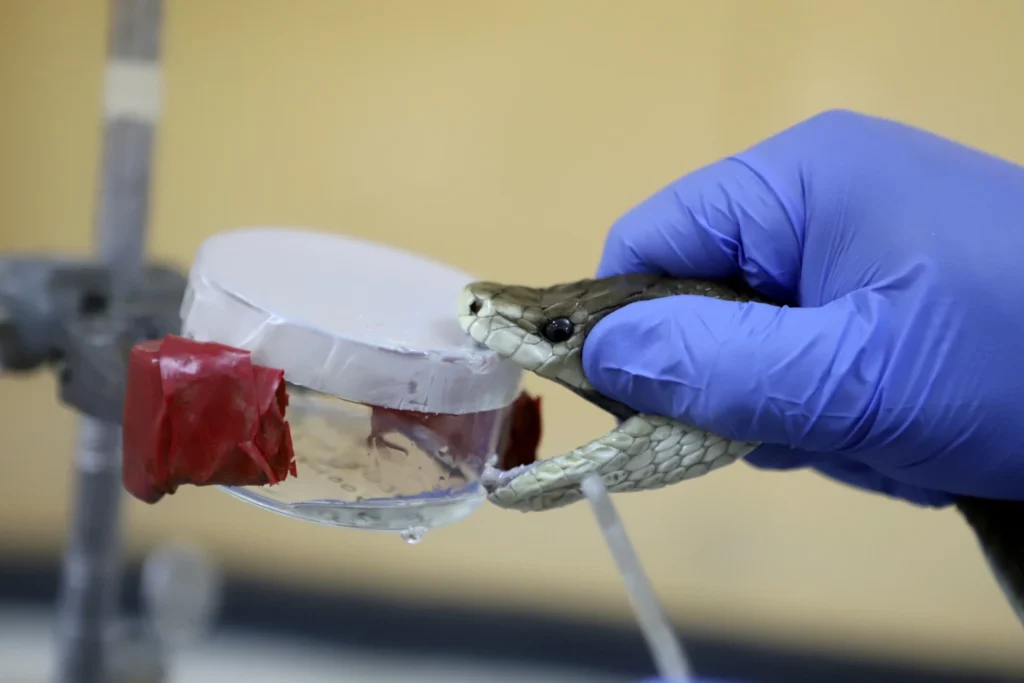

Kenya imports antivenom from Mexico and India, but these treatments are often region-specific, meaning they may not effectively treat bites from local snakes. Part of Maranga’s work involves extracting venom from Africa’s most dangerous snakes, like the black mamba, to help produce the next generation of antivenom.

“The current conventional antivenoms are quite old and suffer certain inherent deficiencies such as side effects,” said George Omondi, head of the Kenya Snakebite Research and Intervention Center. The researchers estimate improved antivenoms will take two to three years to reach the market. Kenya will need about 100,000 vials annually, though it remains unclear how much of this can be produced locally.

The research aims to make antivenom more affordable. Even when available, up to five vials may be required, costing as much as $300.

Meanwhile, the research center conducts community outreach on snakebite prevention, teaching health workers and locals how to coexist safely with snakes, administer first aid, and treat snakebite victims.

The goal is to prevent tragedies like that of Kangali’s neighbor, Benjamin Munge, who died in 2020 four days after a snakebite because the hospital had no antivenom.

“It’s unlikely that snakes will move away from homes,” said Kangali’s mother, Anna. “So solving the problem is up to humans. If the snakebite medicine can come to the grassroots, we will all get help.”