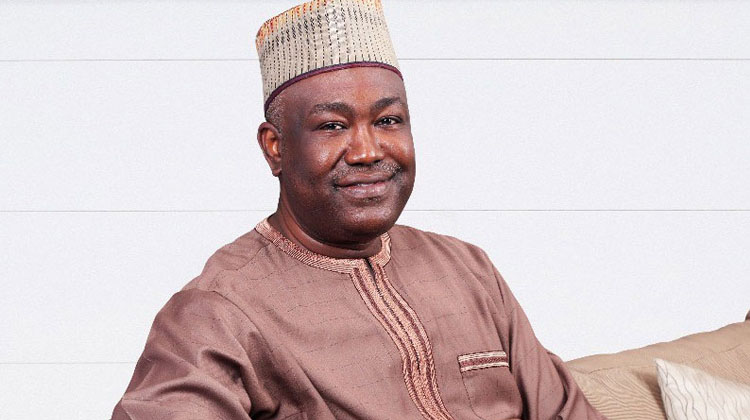

In a recent television interview, Muhammed Sanusi II, the Emir of Kano, shared a personal account of his connection to Nigeria’s former military leader Murtala Mohammed, who was assassinated in 1976. Speaking on Channels Television’s Politics Today, the prominent traditional ruler revealed he was a student at Kings College in Lagos when the coup that claimed Murtala’s life unfolded. The late head of state, he noted, was not only a political figure but also a family guardian who played a formative role in his upbringing.

Murtala Mohammed, Nigeria’s fourth Head of State, was killed on February 13, 1976, during an attempted coup led by Lt. Col. Bukar Suka Dimka. While his seven-month tenure was cut short, his legacy as a decisive leader and anti-corruption advocate remains entrenched in the nation’s history. Sanusi, reflecting on the 49th anniversary of his death, painted a nuanced portrait of the late leader, describing him as “kind-hearted” and “humorous” in private, contrasting his public reputation for sternness.

“Murtala Mohammed was my uncle. My father was in the foreign service, so I grew up under the care of my great uncle, Alhaji Inuwa Wada, who was also related to him,” Sanusi explained. The royal figure recounted moving to Lagos in 1973 to attend Kings College, where Murtala became his official guardian. Weekend visits and holidays at the late leader’s home, he said, fostered a bond with Murtala’s children and offered glimpses of the man behind the military persona. “He had this image of a strong, tough leader, but privately, he was gentle,” Sanusi recalled, emphasizing the disconnect between public perception and familial intimacy.

The assassination remains a pivotal moment in Nigeria’s post-independence history, marking one of several violent power struggles during the country’s military era. Sanusi, who was at Kings College during the attack, described the day as a tragic turning point. While tributes often focus on Murtala’s policies—including the controversial creation of new states and moves to relocate Nigeria’s capital to Abuja—Sanusi’s remarks humanized a figure frequently memorialized for his political boldness.

Murtala’s brief rule saw sweeping reforms, such as dismissing over 10,000 public officials accused of corruption and reducing Nigeria’s dependence on foreign powers. His death triggered national mourning and solidified his status as a martyr for governance reform, though his administration’s abrupt end left many initiatives unfinished. Sanusi’s recollections, however, sidestepped political analysis, instead highlighting childhood memories of meals, stories, and mentorship—a deliberate focus on legacy beyond the barracks.

The interview coincided with renewed interest in Nigeria’s military past, as younger generations revisit historical narratives. Analysts suggest such personal accounts provide vital context for understanding leaders often reduced to textbooks or political slogans. For Sanusi, whose own career has intertwined with public service and controversy, the reflections underscored how familial ties and formative experiences shape perceptions of national history—one gentle uncle at a time.